I tried hard to find any historical connection between us—former Yugoslavia—and them. (Back then, they went by Upper Volta.) But there wasn’t one. They formally shook off colonial rule in 1958, but weren’t quick to embrace “peaceful coexistence,” so they missed the 1961 Belgrade summit where non-aligned nations launched history’s coolest Cold War indie brand. Consequently, our greatest son never visited them—not aboard the Galeb, nor by any other means (landlocked, you see). We might’ve given them a scholarship or two for medical studies, but we certainly didn’t build them highways or dams.

So when I boarded the seven-hour flight to Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso’s capital, I truly didn’t know what to expect. The U.S. State Department’s travel advisory read like pure horror—Level 4: Do Not Travel. Terrorism, crime, kidnappings—not just threats, but daily realities. Jihadists control two-thirds of the country; over two million people (out of twenty million) are internally displaced. Outside the capital, even American diplomats can’t move freely or assist their own citizens. A state of emergency blankets the nation. I was traveling at my own risk—they might as well have added, “Don’t forget to update your will.” Is that all one could say about a West African nation?

Well, there were also the coups—failed ones in 1989, 2015, and 2023; successful ones in 1966, 1980, 1982, 1983, 1987, and twice in 2022 (January and September).

The last one brought a superstar to power.

So I wasn’t surprised when Ouagadougou’s Revolution Square on that late April day felt like a scene from a famous film—crowds, banners, chants, youth, defiance. But this time, the protagonist wasn’t a romantic Latin American guerrilla, the world’s darling, but Captain Ibrahim Traoré: a pan-African military leader with dark sunglasses, a steel gaze, and a facial scar deadlier than any bullet. To hundreds of thousands, he is the new Che Guevara. Only this isn’t the era of ideologies anymore—this, my friends, is the age of narratives. And the handsome young captain (the world’s youngest head of state) wields narratives with chilling confidence.

While the West accuses him of plundering resources, corruption, and repression, his popularity soars—at home and abroad. Traoré’s junta seized power as a “transitional government” (wink) to root out systemic flaws and prepare for fair elections. Yet no elections come, and Traoré says none will soon. When critics point this out (like a U.S. general noting Traoré spends gold reserves on staying in power rather than public welfare), the effect backfires spectacularly—a surge of support! Online, artists, activists, young leaders across Africa and its diaspora, even prominent African Americans, rally behind him.

This chasm between external criticism and internal idolization holds the key to the “Traoré phenomenon.” It stems not from his success in leading one of Earth’s poorest nations, but from the global order’s failure to offer youth anything to believe in. Traoré’s Burkina Faso provides dignity—something no bureaucracy can. Unlike the legendary Thomas Sankara (with whom he’s often superficially compared), Traoré lacks a coherent ideology. He offers social positioning. His rhetoric isn’t theory or plans, but raw grievance. He expelled French troops and diplomats, cut ties with ECOWAS, lambasted the African Union—all while praising pan-Africanism and aligning with Tehran and, inevitably, Moscow. And unlike certain presidents we know, the captain looked downright majestic at Moscow’s Victory Day parade. His message is simple: “Africa is ours. You won’t decide for us anymore.”

With Mali and Niger, Burkina Faso formed the Alliance of Sahel States (AES)—a confederation with shared military, passports, and customs. Like similar global experiments, it seeks an alternative security and economic order, free from former colonial powers. Russia stepped in with advisors and gear while the West flounders in contradictions. Yet as Burkina Faso declares sovereignty, it slides into isolation and dependence on new partners with toxic agendas—”sovereignty” today is stretchier than ever.

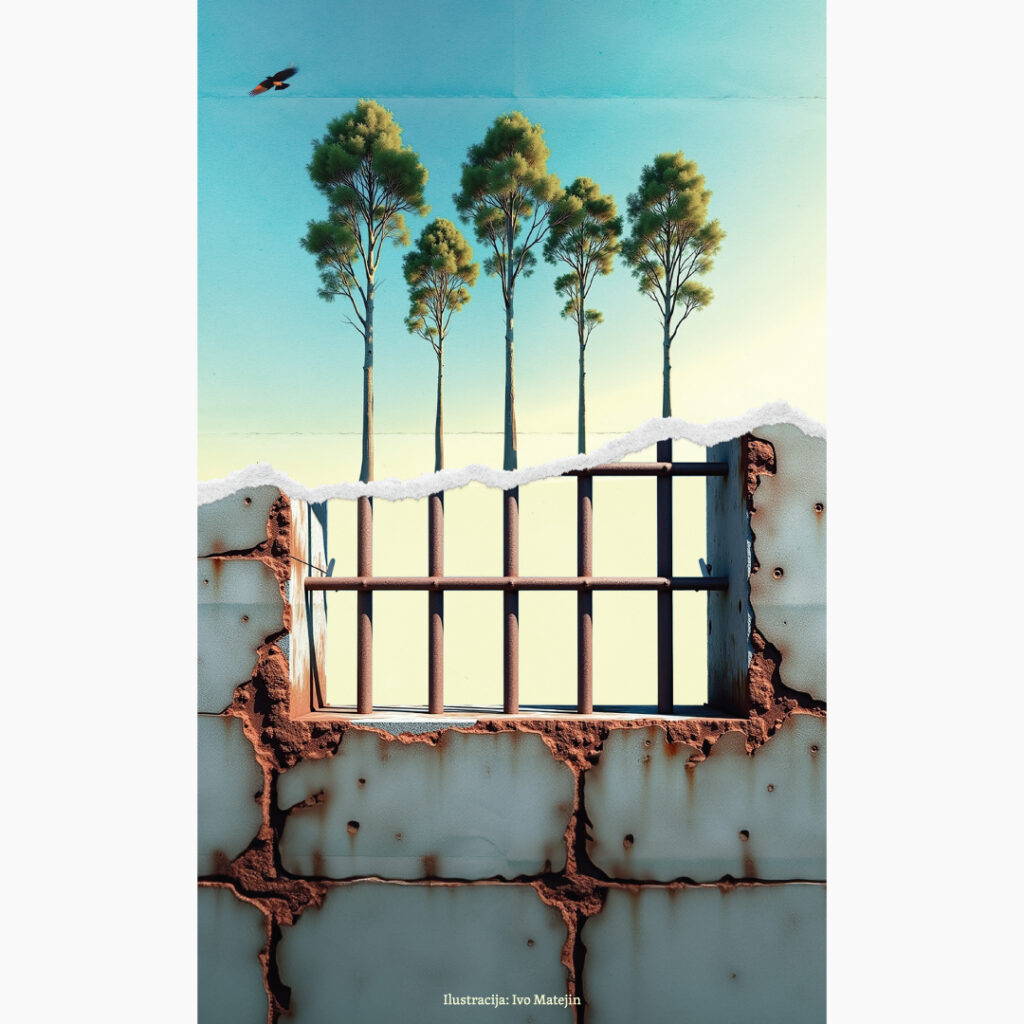

The captain is youth’s darling, but journalists vanish, opposition is nonexistent, and internet blackouts multiply. Military spending jumped 70% while schools close and terrorists claim more territory. Yet Traoré endures, growing stronger. How?

In uncertain times, identity trumps results. You needn’t win—just look like someone who won’t kneel. That’s rare today, not just in Africa. Geography blurs when you’re trending globally on TikTok’s “For You” page. Traoré isn’t just an African leader—he’s a symbol. A symptom of a world where democracy, economics, and institutions mean nothing. The planet craves icons who look like resistance—even if authoritarian, even if they breed more chaos. In that sense, Traoré is a romantic hero—but for a crumbling world, not a hopeful one. A revolutionary for the age of algorithmic revolt, where Instagram outweighs manifestos, and the enemy isn’t capitalism, but emptiness and humiliation.

To learn all this, I didn’t need a transcontinental flight. A scroll through social media would’ve sufficed—let’s be honest, he’s likely not the future, not the next Che.

But he is the pliable, ever-adaptable antihero of our present. And in this world, only such men thrive.